The Campanella Collection of Works by Thomas Hart Benton

An Essay by Benton Scholar Henry Adams

By Circle Auction | Oct 2023

In the summer of 2007, a notable art collecting couple in Kansas City reached out to Henry Adams, the revered Benton author and scholar, to review their collection. Henry Adams spent several weeks in person with what become known as the “Campanella Collection“, 120 original works by Thomas Hart Benton. The entire collection will be offered at auction in Nov. 2023. Adams essay, chronicling the friendship of Thomas Hart Benton and Vincent Campanella and the orgin of the collection is here in full:

The Campanella Collection of Works by Thomas Hart Benton

by Henry Adams

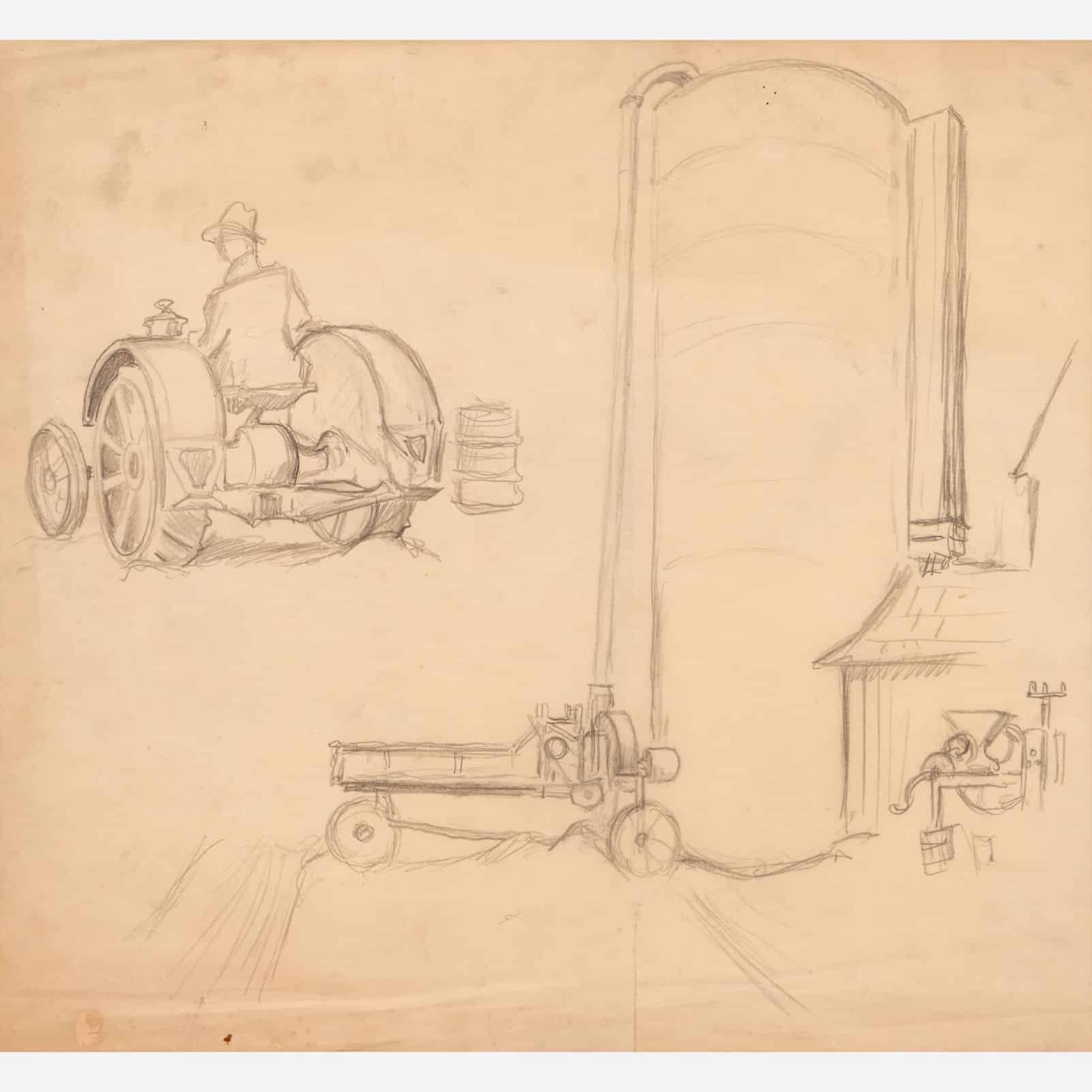

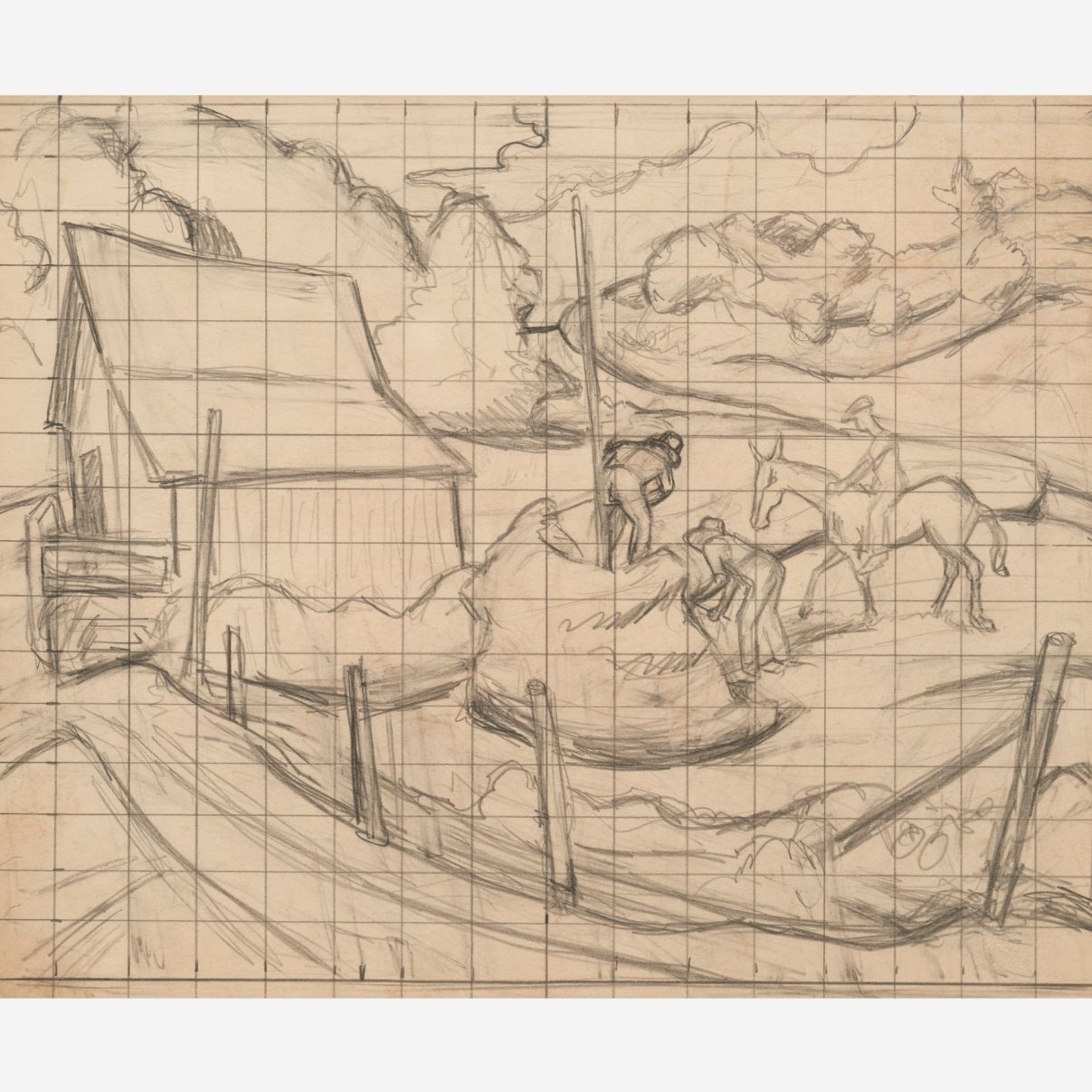

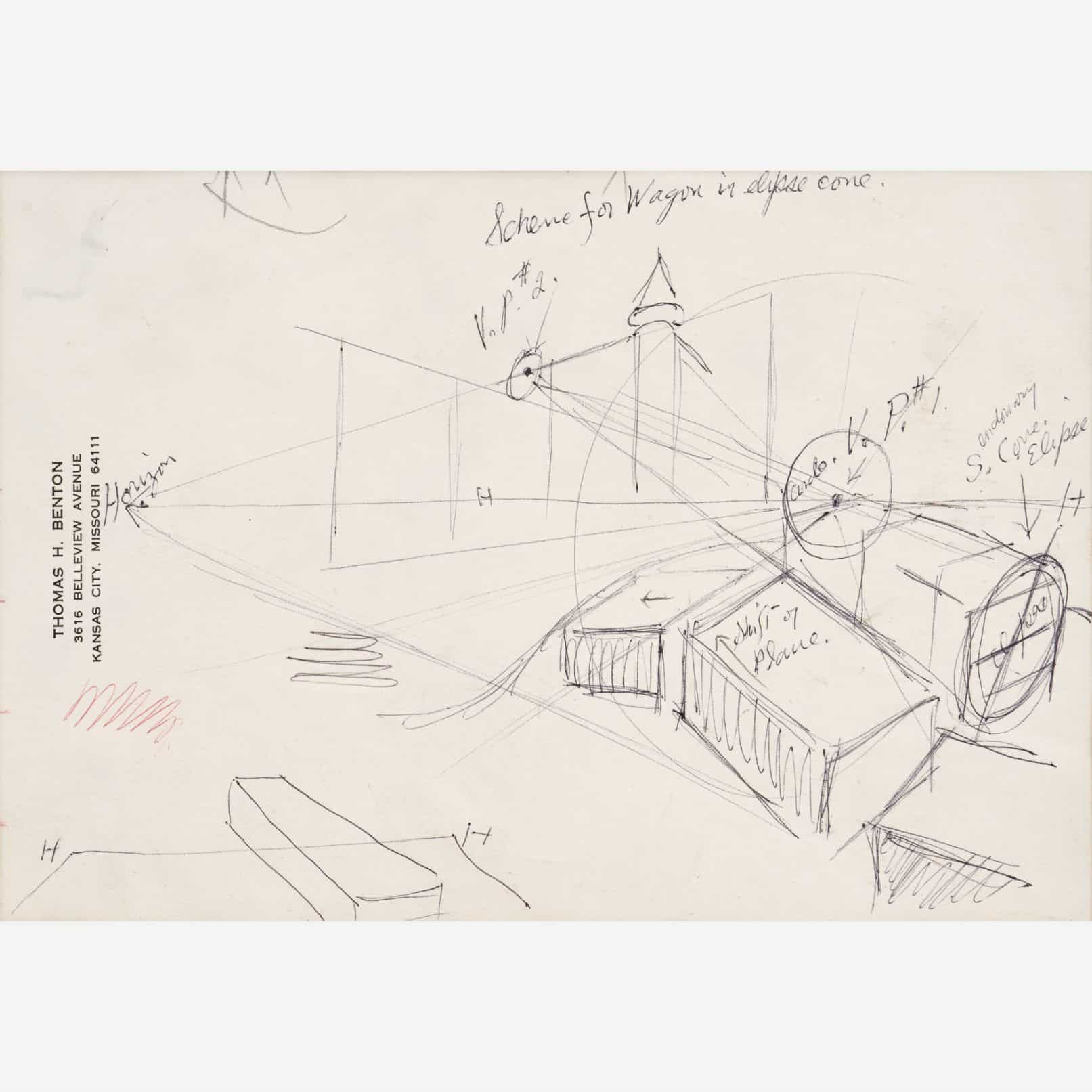

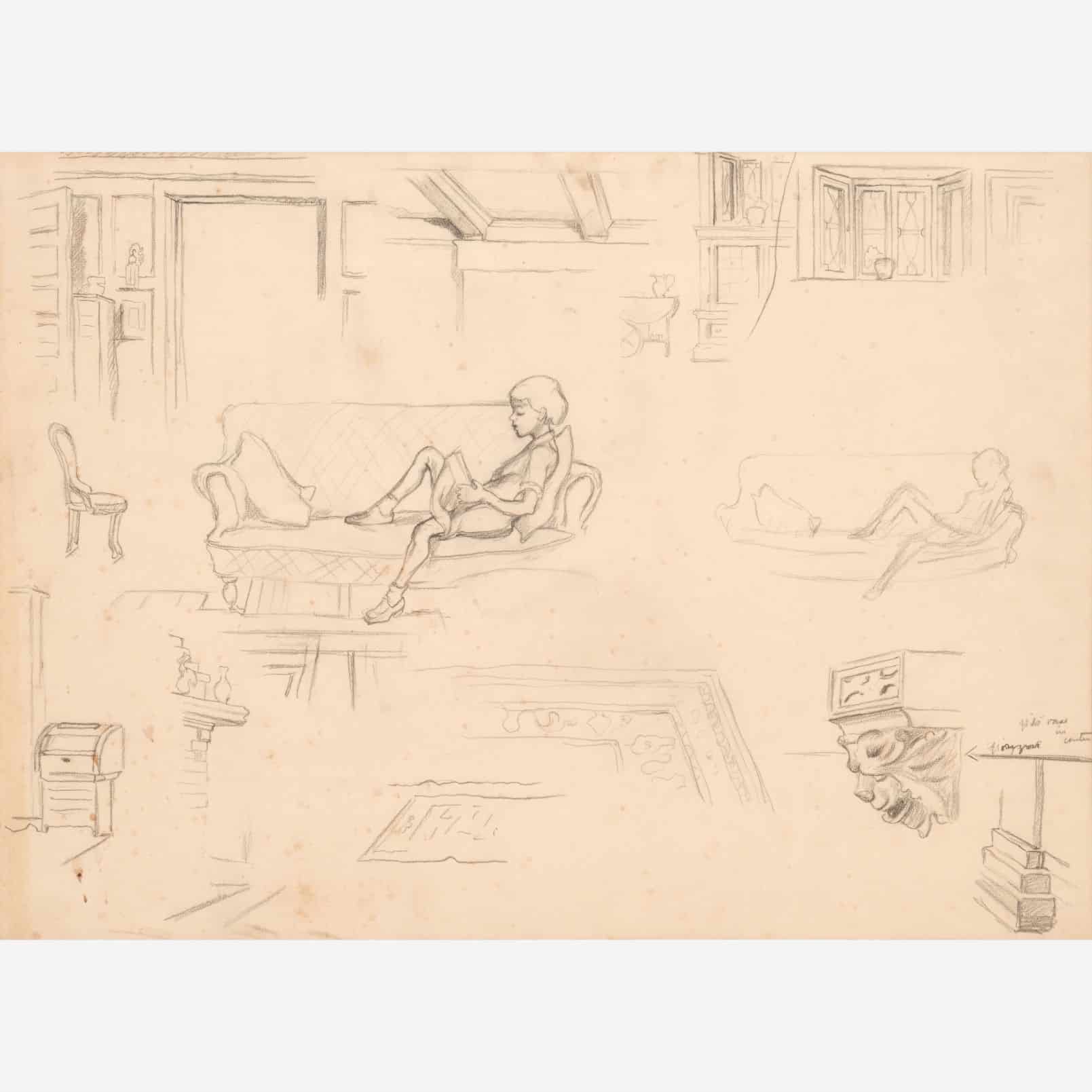

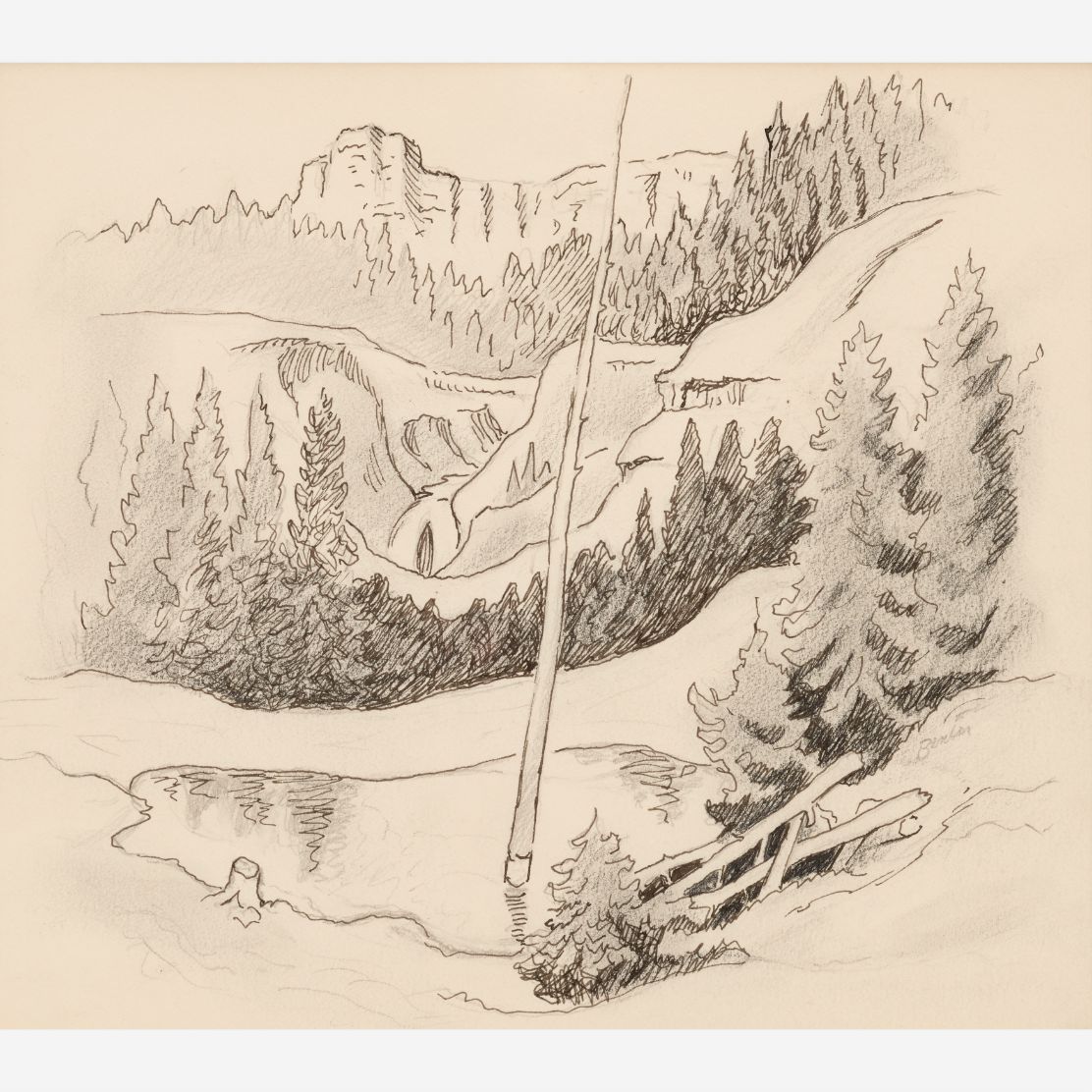

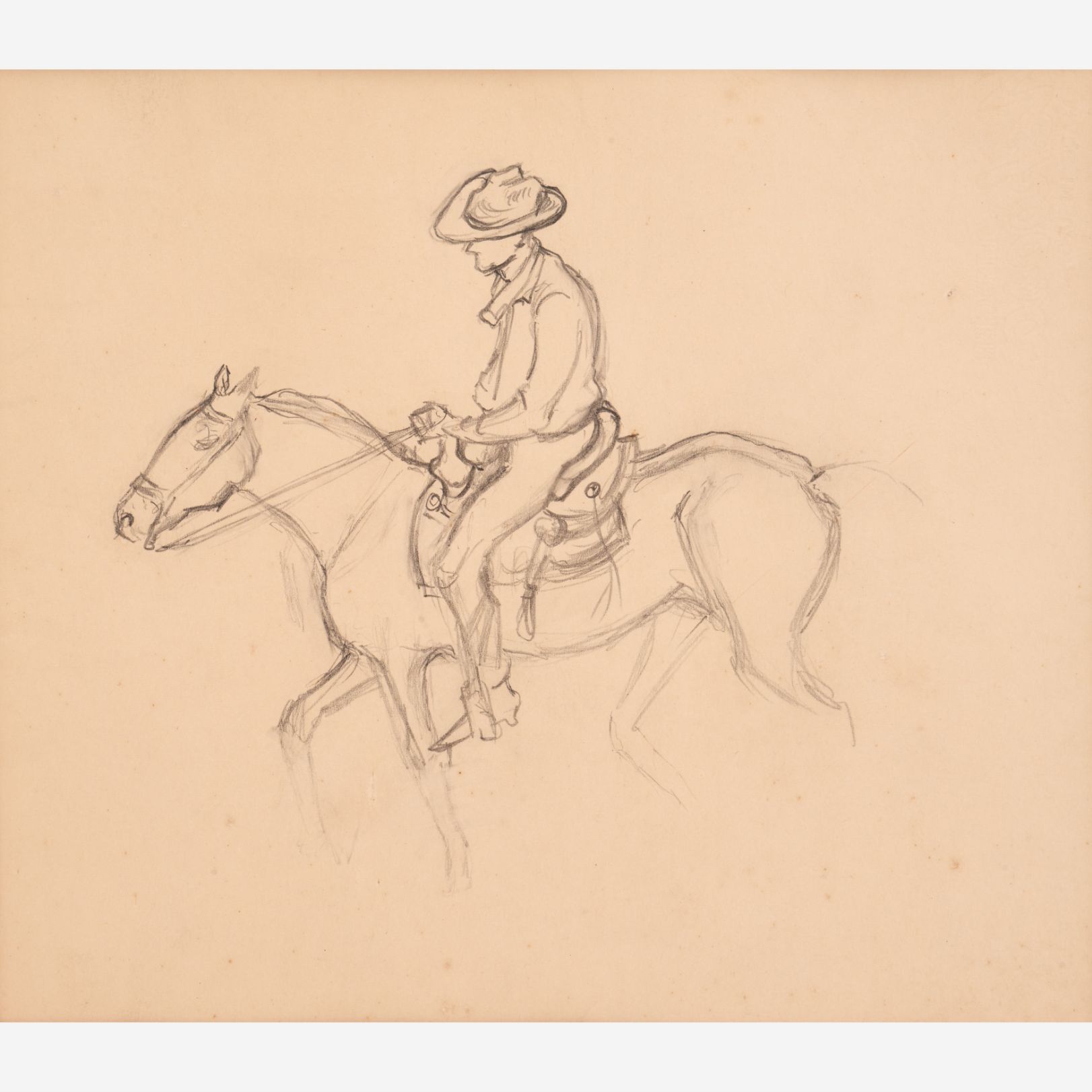

This collection of works by Thomas Hart Benton, assembled by Vincent Campanella, is the single largest collection of Benton drawings and studies outside of the Benton Trust. What is more, unlike the few other large collections of Benton’s drawings that are outside the Trust, such as the one at the University of Indiana, containing studies for his Indiana mural, it is not limited to a particular project but shows the range of Benton’s development over nearly sixty years of artistic activity, from about 1917 to the year of his death.

The Collection’s Significance

Diverse Representations of Benton’s Career:

The collection is fascinating on many levels. It allows one to chart the many changes of style that Benton went through over the course of his career, from early works much influenced by Synchromism and other modern styles to the mature Regionalist work which brought him national fame. No other body of Benton’s work, in a single place, provides such a varied record of his changes of subject matter and style.

In addition, it provides an interesting record of a most unusual friendship. While Campanella never achieved the national fame of Benton, he was a remarkable artist, and one of the most astute and pungent critics of Benton’s work. The story of his own artistic career is fascinating, as is an account of his on-again off-again relationship with Benton.

”

Perceptions of Benton

Campanella’s Complex Relationship with Benton:

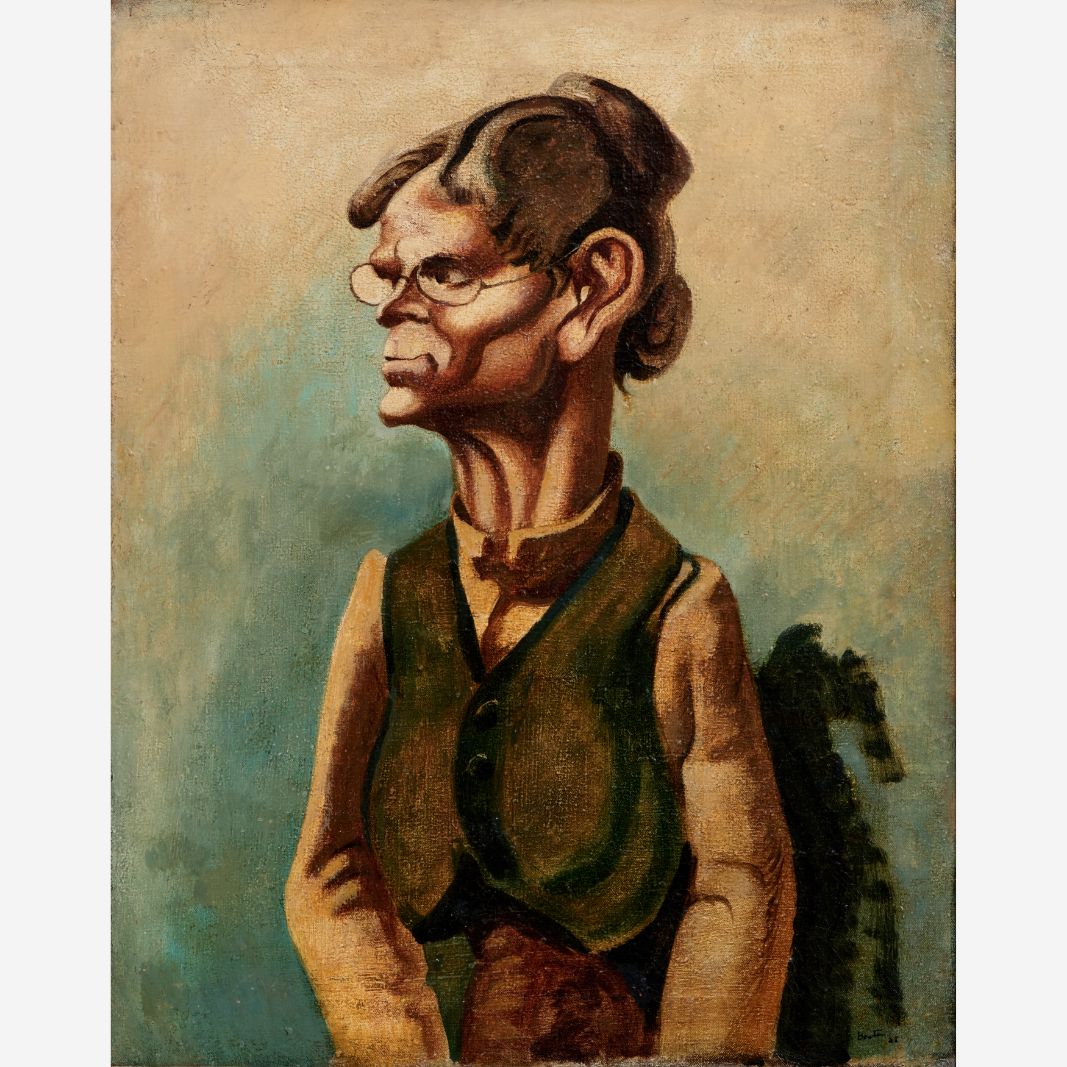

In 1989, when Ken Burns made a documentary film on Benton, Campanella was one of the talking heads who stood out most vividly. Filmed against his own portrait of Benton as a backdrop, with half his face lost in shadow, he looked somewhere between the Godfather of Mario Puzo’s saga and an oriental sage. He spoke in aphorisms, which were at once forceful and slightly cryptic. His shifts of thought were often abrupt, like those in a poem by Ezra Pound, and his words contained implications that often seemed to go in two different directions at once. Throughout the interview, Campanella stressed Benton’s combination of charm and a strange kind of shiftiness.

“Very sociable man. Very warm. Intimate. You met him and you knew him all his life. He’ll make anybody comfortable with him. And yet I think that was a façade. He’s a public image. His family is in politics—he knows how to shake your hand and make you feel welcome. His parties are legion. But as an artist he’s a different person… I think he became a very lonely man.”

While Benton is often pictured as irascible, Campanella saw his denunciations of the art world as a publicity device. Benton simply realized that publicity of any sort helped sell his work.

He became public news, not on the art page, on the front page. It’s better to be called a louse, anything, than not to be mentioned at all….You look in through a Benton painting and in the end you’ll see a very quiet poetic man.

At times Campanella spoke admiringly of Benton.

He worked at his business. He worked at his craft. I mean the business of putting on paint, designing the picture, completing the picture….I think he’s a very fine painter. Excellent painter. I think in time when they strip away his notoriety, they’ll look at him as a painter.

The Duality of Benton: Public Image vs. True Artist

In Campanella’s view, however, in the end Benton’s quest for fame ended up pulling him away from his vocation. “He was concerned with his career, his success, his front page. Takes all this time.” What he admired in Benton was the early work.

He went back and he went through the Ozarks and he sketched. …he wanted to get the feeling of this. He worked very hard at it. And he came up with something that’s stimulating. If you look at the early work, it is stimulating in approach. He paints rapidly. He paints with a lot of decision. Then he gets it…

A real painter—he sees America. The critics talk America. The critics talk all the art since World War II. He saw it. To understand Benton you have to see America too. Shortly after we came here, we went down to Arkansas and by Jesus, I looked around and I said, “Bentonism! This is Benton! He didn’t do a damn thing. He painted what he saw.

But of those who had been friends of Benton, who had known him intimately, Campanella was by far the most critical.

The irony is he does American subject matter with an Italian Renaissance style.. He prospered and in my opinion he decayed, but he became very popular. His work became slicker, smoother, more detailed. And he more lonely… Maybe success is a deadly thing. What to do with success? He didn’t know what to paint after that. He painted success.

There is a certain brutal truth to this, but one can’t help but suspect that there was also a touch of competition and envy in Campanella’s remarks, directed towards a man who achieved a sort of national celebrity that he always wanted for himself but never achieved. At times one wonders whether Campanella was truly a friend. But perhaps the most startling moment in the film comes when Campanella recalls Benton’s death. At this point he suddenly breaks down into tears. Did he like Benton? One senses that Campanella himself wasn’t quite sure. But life without Benton was a diminished thing.

The Life of Vincent Campanella

Early Years and Artistic Beginnings:

Who was Vincent Campanella? What was his artistic background? Born in New York City to Sicilian immigrant parents, Vincent Campanella grew up in a tough section of town known as Hell’s Kitchen. At an early age, art became his escape. His older brother gave Vincent a watercolor set for his fourth birthday and by age seven Vincent had proven so precocious that he was presented with the Wannamaker prize for young artists by Mayor LaGuardia. Starting at the age of nine he began attending the Leonardo Da Vinci School, where he received rigorous academic art training.

The school was directed by a conservative Italian sculptor, Attilio Picirilli, and it carried on the conservative methods of the Naples Academy. As an adolescent, Campanella virtually lived at the Da Vinci School. He did his schoolwork in the principal’s office and had his own key to get in on weekends. He was coddled by the teachers and got all the scholarships. By the age of twelve the teachers were ready to send him to Europe for further training, but his father thought he was too young. So he went to the National Academy of Design for a couple of years, from 1931 to 1933

By this time he was already an accomplished master of the human figure. Writing of the works in the 1995 retrospective of Campanella’s work, Robert Morris noted:

The largest painting is from 1931 (The Baker) painted when Campanella was 16. This is a vertical picture—a study of a male nude seen from the back. The flesh and bulk of the figure have an extraordinary life. The paint and the human form reverberate against each other in a way that is reminiscent of Eakins.

This stint at the National Academy ended his formal training. Just eighteen years old, Campanella then struggled to make a living as an artist. He briefly held a job that earned him six dollars a week; then briefly held another that earned him twelve. For a time he had a studio in the middle of the Loft District that is now Soho. Then he moved to Midtown, Manhattan, to a place that had no water and or heat but cost only ten dollars a month. He began showing his work at the Ferargil Gallery, which also handled Benton’s work, and had a space for young artists downstairs.

Through the gallery he got to know someone who worked in the New York City Relief Department, who told him to apply for public support. As Campanella recalled:

“He said go down there and apply and don’t expect to hear back from them. After a day or two go back, because if you don’t go back they’ll figure you don’t need it so bad.”

Campanella and the WPA

Finally someone showed up at his studio and put him on City relief. He then went down with his relief card and showed it to the WPA. They asked him to bring in some paintings so he brought in some watercolors he had done at the Leonardo Da Vinci School and single oil. Impressed, they put him on the Easel Project—the most desirable category since it gave him freedom to work on his own. They would give him an assignment and he would have three weeks to complete it if it were watercolor or six if it were oil. Less accomplished painters were given subordinate positions, for example, to serve as a mural painter’s assistant. You could get materials for free, including wonderful watercolor paper of 300 pound weight. Even free models. As Campanella recalls:

Models meant women. Naked women. I did that only once. I figured I wouldn’t have any time to paint.

To try to ensure that people put in a full day of work, the WPA had you show up every day at 9:00 at an office they had in the Seventh Regiment Armory. Once you had checked in you were free to go back home and catch up on your sleep. Campanella ultimately got around this by arranging to go to Gloucester and Rockport on painting assignments. He would go up there for three or four weeks and then bring back his paintings. But this sort of freedom didn’t come easily—he had to fight for it.

In addition to his painting assignment, he volunteered to work for the artist’s union, collecting dues. On one of these collecting missions he met Elaine de Kooning, who was working as a muralist’s assistant, since she didn’t qualify for the Easel Project.

In 1939 he took on a travel project. His assignment was to go out to Rock Springs, Wyoming and organize a little community of 8,500 to be art conscious. Most of the people there had never seen or heard an artist in their lives. As Campanella later stated:

When I went out there in my Model A. Ford I stopped at Laramie, at the University of Wyoming. The head of the department said: “You’re a 20th-century pioneer and your wagon is your Model A. Ford. You’re going out to do what nobody ever did before.” And it was true.

Organizing had rough moments. At one point, when Campanella and a small group of other artists were picketing for jobs, the police arrested them and hauled them into court. According to Campanella’s account, he and his friends gave their names as Botticelli, Piero Della Francesca and Cezanne. Taking the hint, the judge showed leniency, telling them to go back to their studios and stay off the street. Campanella always felt considerable pride that the Fine Arts Community Center which he established in 1939 still exists and is still active. Some of his private students went on to notable careers as artists.

His hard work caught the attention of the top brass in Washington. Holger Cahill who ran the Federal Arts Project, heard of his work and invited him to stop by to see him. So on his next trip to New York, Campanella took a detour through Kentucky that brought him to Washington and somehow found Cahill’s office. As Campanella later recalled:

When I got to his office I said, “I’m Vincent Campanella.” He said, “Sit down! Sit down! We get so many letters from Wyoming that we wonder if you’re going to run for governor!”

Along with organizing, he worked on his painting, soon discovering that the methods he had learned at the Da Vinci School and the National Academy of Design were no longer adequate.

Being in Wyoming changed my art life. I found in Wyoming my technique didn’t work. I knew everything up close but I didn’t know how to paint things that were far away—and huge. Ever been to Southern Wyoming? You look at a distant field and it’s forty miles away. How do you make forty miles on a flat surface?

In 1940-41 he served as artist-in-residence at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, but this position proved short-lived. As Campanella recalled:

What was the former Senator from Wyoming named? He was always attacking social security. His father was on a rampage in Wyoming against liberals. He made the President of the University fire someone who was a liberal. Whatever that meant to him. I had just been hired. The looked through the roster and found the name Campanella. So they fired me without even seeing me.

With impressively skewed logic, he was told that they were purging the campus of Fascists.

I went back to my little town of Rock Springs and told the superintendent of schools who knew me pretty well and he said, “Boy, he got that cock-eyed. If anything you’re the opposite.”

During the war he worked in industry, developing innovative machining procedures. But after the War he declined offers to executive positions t o go back to art. “What I liked about mechanical problems,” he noted, was that there was always a solution. What I liked about art was that there was never a solution.”

In 1946 he returned to Rock, Springs to paint a group of western landscapes, with generalized blocky shapes and a muted palette. Like the work of Marin, they explore the dynamism of forces in the landscape, and their vocabulary shows some knowledge of Cubism. Robert Morris has noted:

A painting of a mountain (Bach) seems to be one of Campanella’s favorite pictures and was painted in 1946 in Rock Springs, Wyming. It is obvious that the Wyoming experience was pivotal for Campanella. Some impulse of the American Sublime that reaches back to Church and Cole may play itself out in these depictions of tcrags and mountains of the West. This is a modest sublime without the bravura, scale or utopian overtones found in earlier American art.

Struggles, Achievements, and Associations

From 1947 to 1949, Campanella taught at Columbia University in New York City. After attending an exhibition of the work of Cezanne at the Wildenstein Gallery he became fascinated by Cezanne. As Campanella commented:

I saw the brushwork and I thought this guy loves to paint. I changed. I took my class out to Riverside Park. I looked up and saw a Cezanne looking me in the eye.

Throughout his early years, Campanella was a prodigy, who always associated with painters five or ten years older than himself. Notably, between 1945 and 1949 Campanella had three exhibitions at the celebrated Rehn Gallery in New York. Campanella walked in off the street with some examples of his work and Rehn said “You’re terrific—you’re a painter-and I’ll give you an exhibit.” Rehn was one of the leading dealers of the 1930s, and had many famous artists in his stable, including Edward Hopper, Charles Burchfield, and Reginald Marsh. “Rehn was so kind to me,” Campanella recalls, “and he never charged me for an exhibit.” But Campanella’s timing was off, since taste was changing towards abstract painting. “I was in the wrong company. This was in the late 30s and everyone was going somewhere else. They were going to Peggy Guggenheim.”

A few years earlier, Edward Hopper had also come in off the street, when Rehn was going out to lunch, and had asked if he would look at some paintings. When Rehn saw them he immediately agreed to take his work. When the show opened, he sold every single piece. He told Campanella that “I’m going to handle you the same way I handled Hopper and the same thing will happen.” But this proved wishful thinking.

Campanella’s second show with Rehn was one of watercolors. As Campanella later recalled:

Hopper was having a rare show in the main galleries. So he said I’ll put you in the second gallery so people will see them as they walk through. But they walked right through.

In contrast to the work of the Abstract Expressionists, who were developing a completely non-objective style, Campanella abstracted from the forms of nature in a fashion reminiscent of other romantic painters of the period such as Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley and Karl Knaths. While sales were modest, he did get brief notices in national art magazines such as Art Digest and Art News, where he was often categorized as a “Western” painter. One reviewer described him as “a discrete Milton Avery who builds his compositions around the natural grandeur of the Rockies.” Another noted that his watercolors “present moody interpretations of two widely-separated but similarly rugged regions—the rocky shores on Mongehan and the ranges of Wyoming.”

In 1949 Campanella moved out to Kansas City where he taught for three years at the Kansas City Art Institute. In 1952 he took a new position nearby at Park College. He taught there until 1980 and stayed on as professor emeritus for the next two decades. By all accounts he was an exceptional teacher, provocative, unpredictable, difficult, but also encouraging, and a lifelong source of inspiration to many of those who knew him.

Jean Burnham Morganthaler belonged to a group of women painters who took private lessons from Campanella from the 1950s to the early 1970s. She recalls that his critiques were sometimes scathing. She later recalled: “I think it took several years for me not to tremble when he came to me. As the years went by I realized he was really a very sweet, though opinionated, man.”

Over the years he has had several notable students, including the noted minimalist sculptor and theorist, Robert Morris (whose sculpture Bull Wall is placed near the stockyards in Kansas City), the cartoonist, xx, and the art historian Burton Dunbar, who now serves as Chair of the Art History Department at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. Morris arranged a retrospective of Campanella’s work at Hunter College in New York in 1995.

During the summer Campanella lived in Owl’s Head, Maine, where he produced dark moody watercolors of the coast and forest, such as Cathedral Woods of 1955. His last sustained period of painting ended in 1955. During this period his productivity slowed and his work grew increasingly abstract. Robert Morris notes:

He had made no paintings to speak of since the late 1950s. The picture White, dated 1992 is an exception. It is an almost completely white picture—a landscape of ambiguous shapes that recalls the style of the late ‘40s pictures. Perhaps it is a snow storm. Or perhaps it is a kind of ghost picture that represents all the absent pictures he did not paint for 40 years. Unidentifiable objects hover in this albino space. It is a barren but dense landscape: a haunted, reverberating space that suggests a metaphor for both mourning and bearing witness. Perhaps artists need a minimum of love and attention to go on after they have passed the fiery youthful years where the fullness of the self bulls forward with little need of support.

A Shift In Focus

By this time, Campanella seems to have given up struggling to achieve artistic celebrity. His showings with the Rehn Gallery marked the high point of his reputation as an artist. After his last solo show there he never established another association with a commercial gallery. After a final solo exhibition at a regional museum in Topeka, Kansas, in 1956, he ceased to regularly exhibit his works.

In many ways, Campanella was a casualty of the change of sensibility that took place in American painting after World War II. “Everything was so easy in the beginning,” Campanella once commented. “I won all the prizes.” Much of his mature work is caught between two sensibilities: that of the Regionalist interest in the specific rural place and the Cubist one of structural pictorial order based on the dynamic overlap of planes. But he never fully accommodated to the change in taste that took place when Abstract Expressionism burst on the scene in the late 1940s: he never quite made the shift from an art based on craftsmanship, such as those he absorbed as a boy at the Da Vinci School, and an art based very largely on politics and theory.

Well aware that words and theories were enormously significant, in the 1950s Campanella largely shifted from painting to art-writing, philosophy and esthetics. In 1956, when he was forty-three, he got a Master’s Degree in Philosophy at the University of Kansas, and for many years after that he pursued a doctorate in Philosophy, finally abandoning the project around 1967. For some 45 years he worked intermittently on a book about esthetics and politics. He did not speak much about it but if questioned would reply that it was “almost finished.” The project was still incomplete at the time of his death. “Art is like the ocean. The farther you go in, the deeper it gets,” Campanella once said to a reporter for the Kansas City Star, ascribing the quote to the Renaissance painter Tintoretto.

Campanella’s Relationship with Benton

First Encounters and Growing Bonds:

Campanella and his wife Leah met the Bentons in September of 1949, soon after they moved out to Kansas City. At that time Benton was sixty years old and Campanella thirty-five. Benton had formerly been on the faculty of the Kansas City Art Institute, and while he had been fired by the board he still maintained a friendly relationship with many of the faculty and students.

At this point Benton was still regarded as a figure of national stature and in Kansas City he was a celebrity. He was often written up in the Kansas City Star and he entertained a wide circle of friends, including influential bankers, lawyers, politicians and businessmen. He attended concerts and Kansas City University events of a cultural nature. His home was also a stop-off point for celebrities visiting Kansas City, such as the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, or Norman Thomas, the perennial Socialist candidate for President. In the spring Benton took off with his drinking buddies and canoed on the Buffalo River. In the summer the Bentons closed their Kansas City home and spent several months on Martha’s Vineyard, where they maintained the same active social lifestyle.

While Benton’s social life was busy he never stopped painting but maintained a regular work schedule. He was out in the studio by early morning and worked until noon. Then back to the house for lunch, a martini, and a short nap. Then back to the studio where he worked until four o’clock. At that time he would break for his first cocktail of the evening and friends would begin to gather. Campanella’s wife Leah recalls:

Vincent had a more intimate and close relationship with the Bentons than with the other Institute faculty. First they liked him because he was of Italian descent as Rita was. Benton loved Rita and all things Italian, from food to art to music and of course Italian people. Benton was also very knowledgeable about classical music art, philosophy, etc. and he and Vincent would converse in these areas. And also Benton had a high regard for Vincent’s art training which was at the Da Vinci Art School in New York, which followed the classical tradition modeled after the Naples Academy of Art. The people who established the school were Italian businessmen and well known artists (Piccirilli brothers, who sculpted many national monuments in New York and Washington D.C.). Both Rita and Tom knew the founders of the school having had contact with them when they lived in New York City in the thirties.

By this time, in the New York art world, Benton was already considered passé, since Regionalism had been displaced by Abstract Expressionism. Just two years before, H. W. Janson, who became the author of a best-selling History of Art, had compared Benton and Grant Wood with the Fascist artists patronized by Hitler. Due to his wife Rita’s skills as a business manager, however, Benton continued to sell his paintings and to receive major mural commissions. He didn’t need a gallery in New York or the approval of the New York critics.

A Rift Between Benton and Campanella

But the winds of change were beginning to reach Kansas City as well. On April 17, 1951 the lawyer Lyman Field organized a Forum on Modern Art under the auspices of the University of Missouri, Kansas City, whose President, Clarence Decker, was a good friend of Benton’s. In addition to Benton the participants included Campanella, who represented the Art Institute; Professor Scott who was head of the University of Kansas City Art Department; and Sidney Lawrence, a representative of the Jewish Community Center, who was also an art critic and art historian. Benton was clearly the most famous of the group and everyone expected fireworks, since he was well-known for his denunciations of modern art and its supporters. The auditorium was packed and there were reporters from the Kansas City Star.

As the evening developed it became largely a two man argument, between Campanella and Benton, with Campanella speaking on behalf of modern art. Both were articulate but Campanella more than held his own in the debate, as the newspaper account reported later. The Campanellas soon heard that Benton was offended and the relationship between them and the Bentons abruptly changed. Leah recalled that “They didn’t exactly shun us but Vincent was no longer favored by the Bentons in their previous warmth and affection.” Vincent later claimed, no doubt with some exaggeration: “For twenty years Benton never talked to me. His wife made sure.”

In 1973, however, a mutual friend invited Vincent to drop by the Benton home. Vincent did so and Tom greeted him as though nothing had ever happened, and invited him to come again. Vincent did so and they quickly became close. They even celebrated birthdays together since Rita had a January birthday and Vincent’s birthday was close to the same date. One evening, Benton invited Vincent to paint his portrait.

“When?” Vincent asked.

“Tomorrow.”

At the time Vincent was teaching at Park College, but he made an excuse to come over in the afternoon after his classes were over. Benton talked while Vincent worked. “He’s the most charming guy in the world,” Vincent later recalled. “He can talk you off your feet. And he can sell you anything. I liked him very much.” Both Benton and his wife praised the final painting and tried to get a friend in California to buy it, though without success.

At one point while Benton was posing, Benton got up to take a phone call. When he returned he told Vincent that the country music star Tex Ritter had just called to ask him to do a mural for the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Campanella’s new friendship with Benton lasted only slightly over a year. In January of 1975 Campanella was watching TV with his wife when the announcer stated that he had bad news. Campanella turned to Leah: “I bet it’s Benton. He died.” His guess was right. A few hours before, Benton had died of a heart attack in his studio. It was ten o’clock and a very cold wintry evening, but Campanella walked over to the Benton home to ask if there was any way he could help. They asked him to come back the next day.

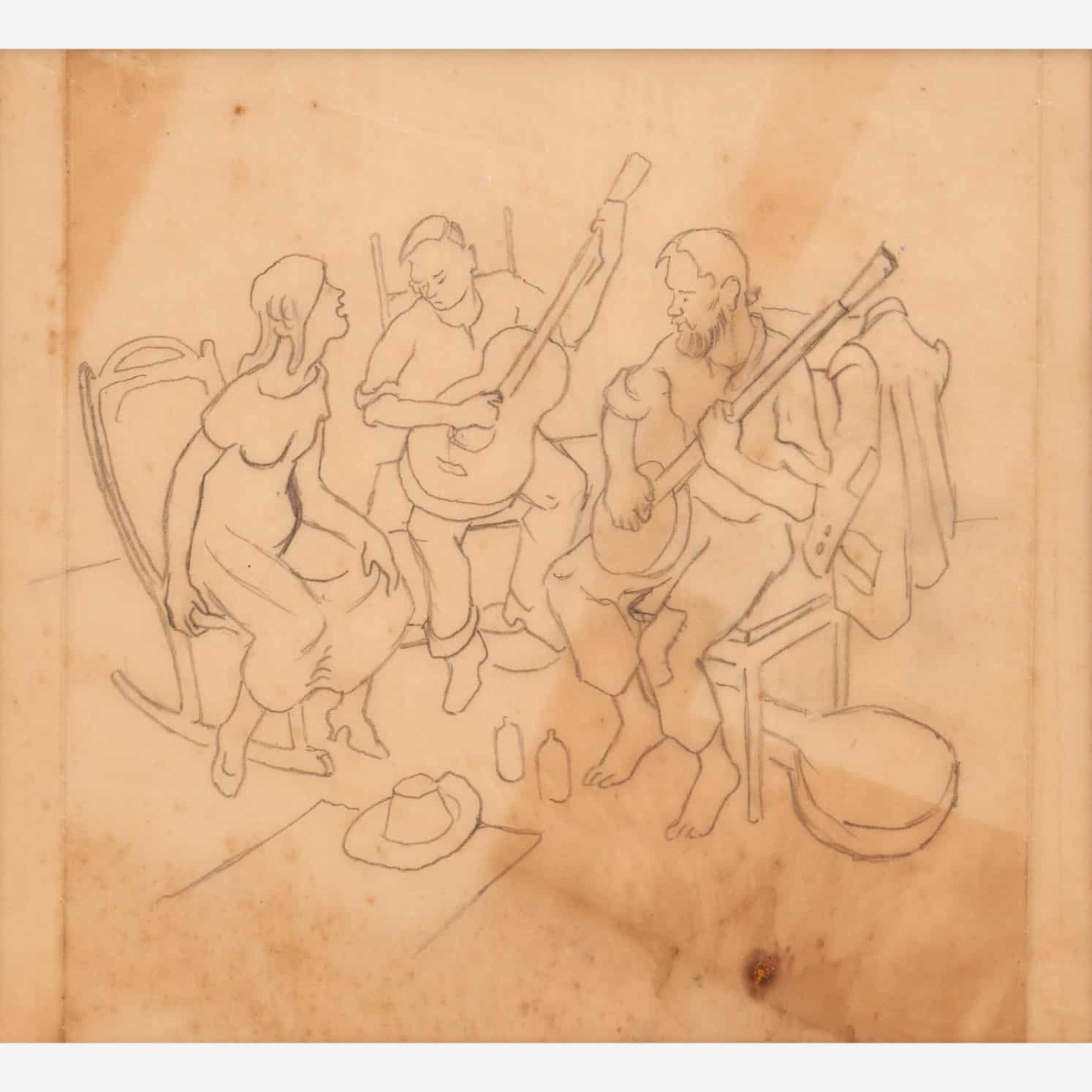

Thomas Hart Benton’s Final Mural

When he walked over to the home the next morning, Rita asked him to take a look at Benton’s mural. It wasn’t finished and the people who had commissioned it were due to visit with a few weeks. Since Benton had been eighty-five when he took on the assignment, they had written a contact which gave them the option of pulling out of the project if the work were unfinished. Naturally, Rita wanted the work to be complete and she asked Vincent to finish the work. There were still some places where the paint did not come up to the edge of the outlines or where the shading was incomplete. Vincent cleaned up the edges and finished off the shading. In places one can discern his additions since their techniques were somewhat different. Benton tended to simply darken the form where it went into shadow, whereas Vincent, following the model of Cezanne, liked to change color. There’s one spot where Vincent’s additions are particularly evident.

Campanella did not usually work in acrylics, but he knew that freezing temperatures would make them misbehave. This was January without heat in the studio, and he was afraid that the painting would develop bloom—that the temperature would make the surface look muddy and disfigured. Consequently, he persuaded Rita to install a gas furnace. “Can you imagine?” he once commented. “Benton spent his life in a cold studio and when he died she got a heating system put in.”

There was just one place where Campanella made a significant change. The main figure on the right hand side of the painting is a guitar player, modeled on Tex Ritter, who had just died. Guitars have six strings but for some reason Benton had put in only four. Vincent squeezed in two more strings, leaving a big space for the string that Tex was plucking.

Interestingly, a legend exists in Country Music circles that Benton painted the wrong number of strings, but when the painting was unveiled the number was correct. The way the story is generally told suggests that there was some sort of celestial intervention. The truth of course is more prosaic—that Campanella added the missing strings.

The Campanella Collection

Campanella must have acquired most of his Benton paintings during the 1970s. According to Leah Campanella, “At some point during this period Tom gave Vincent some painting and sketches that were not a part of the family collection.” Perhaps some of these paintings were given to him after Benton’s death by Rita Benton, in return for his work completing Benton’s Sources of Country Music. As has been noted, what is most notable about these works, viewed as a group, is their variety, in style, in subject matter and in date. Not strictly a connoisseur’s collection, since the works vary greatly in finish and even in quality, it reveals instead an artist’s interest in Benton’s working methods, and in the nature of his artistic development. It provides an extraordinary picture of Benton’s development, as well as a record of one of his most intriguing friendships.

Essay by Henry Adams, Benton scholar and author, 2007.

———————————

The entire Campanella Collection of 120 original Thomas Hart Benton works featuring 9 paintings and 111 sketches will be offered at auction Nov. 3rd – Dec. 2nd 2023. You can view the entire collection and sign up for the auction here.

MORE ARTICLES

Jewelry

JEWELRY Fine + Designer + Antique Ended May 3rd Shipping Info Circle Auction is excited to present our yearly dedicated Jewelry auction; composed of fine, designer, antique, and Native American jewelry collections from around the Kansas City area. Designer...

Summer Modern + Contemporary

Contemporary + Modern ART & DESIGN | Aug. 9th - 24thREGISTER FOR THE AUCTION Circle Auction is currently assembling our next event focused on modern design and contemporary art, consigned from various collections in Kansas City and around the region.Current design...

Rare Paul Evans Studio Cabinet At Auction

Unveiling a Masterpiece: Rare Paul Evans Studio Cabinet at Auction By Circle Auction | Jan. 2024 A masterpiece of mid-century modern design is headlining Circle Auction's first Modern + Contemporary auction of 2024. A rare sculpted bronze cabinet by the legendary...

Auction Results from Thomas Hart Benton Collection of Original Works

Auction Results from Thomas Hart Benton Collection of Original Works By Circle Auction | Dec. 2023 Campanella Collection of Benton Works Kansas City's Circle Auction concluded the sale of 113 original Thomas Hart Benton works this past December. The...